We have received messages from several people who participated in the filming.

Born in Niigata Prefecture in May 1925 (Taisho 14)

(100 years old as of 2025)

War is wrong! Killing is wrong! It is wrong for people to be killed in war!

Born in Manchuria in 1936 (Showa 11)

(88 years old as of 2025)

My father died during internment in Mongolia.

Last month, on July 8, I was invited to represent the bereaved families at the memorial service attended by Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress. However, even 80 years after the war, the wounds have not healed.

War is cruel. It completely destroys human happiness.

I pray that there will never be another war.

Born in Tokyo in 1935

(90 years old as of 2025)

My mission is to convey to future generations why Southern Sakhalin, which is officially Japanese territory, was suddenly seized.

The important thing is that Southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands are currently occupied by Russia, but they are not Russian territory.

On internationally recognized maps, both Southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands are left blank, showing that they have always been, and remain, official Japanese territory.

Young people today are often unaware of this, so I urge them to learn about it.

Born in Tainan City, Taiwan, in 1934

(90 years old as of 2025)

After the war, the GHQ came in and changed the education system, and even now, people are made to believe that “the Japanese committed terrible wrongs.”

However, what I want to convey especially to young people is that the Japanese are a great people with the spirit of Yamato, and I want them to live with confidence and dignity.

And now, since Japan is in danger of losing its identity, please protect Japan.

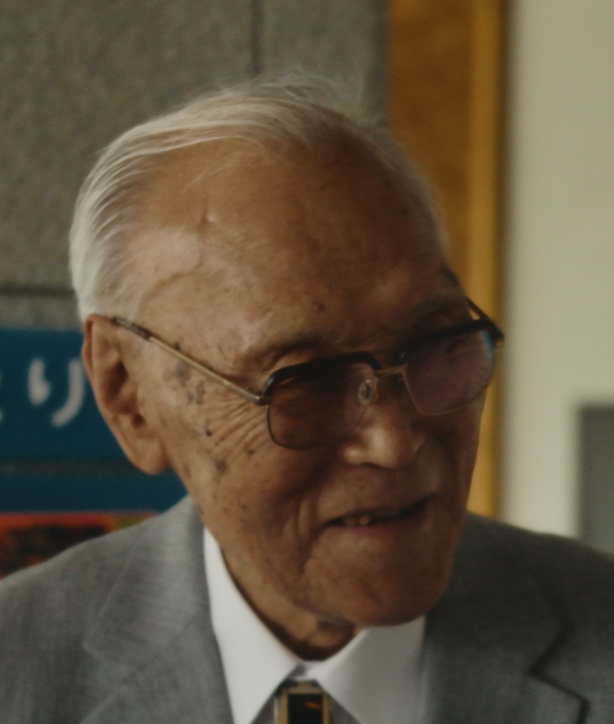

Born April 7, 1934, in Iwate Prefecture

(91 years old as of 2025)

I lived through the prewar, wartime, and postwar eras, and now I am fortunate to be alive in the peaceful Reiwa era, for which I am deeply grateful.

Lately, whenever I hear the phrase “80 years since the end of the war,” the sad memories of my childhood during the war come flooding back.

When the air raid sirens sounded, we would run to hide in the mountains. This happened many times a day, and we lived in constant fear. Food was scarce, and we were always hungry. My friends and I would pull carrots from the fields, wipe them clean on our clothes, and eat them. Just chewing on them was enough to fill us for a short while. Rice gruel with radish leaves and wild herbs was our daily meal, and the only time we ever saw white rice was once a year on New Year’s Day. Those early Showa years were truly harsh.

In the Reiwa era, whenever I shared these stories with my family, they lightly suggested that I should write them down, even just as fragments (which leaves me a little dissatisfied).

Who would bother to read what I wrote?

And even if I did, what good would it do? (It would only strain my shoulders.)

So I often muttered to myself, “I might as well give up.”

But now, after eighty long years, the war experiences that had been pressed into my heart like a heavy lump have made me want to trace back through my distant memories and finally write them down—encouraged once again by my daughter and grandchildren.

At the time, these were the slogans everyone lived by:

“One hundred million hearts beating as one.”

“We will not ask for luxuries until victory is ours.”

With this spirit, people united their hearts, surviving on rice gruel made from radishes and wild herbs. Even as a child, I understood those words. Despite the food shortages and the ragged clothes, no one complained. Everyone held firmly to the belief that Japan would surely win. No matter what misfortunes came, people trusted that the kamikaze—the “divine wind” of legend—would blow again and lead Japan to victory.

But as the war neared its end, B-29 bombers began flying low across the sky. One day, a neighbor who was weeding the fields was struck by gunfire and killed. My mother said to me, “That could happen to us at any moment. Stay close to me.” It was terrifying.

♪ Bravely we swore, “We will return victorious,”

And left our homeland behind.

How could we return without honor?

Each time the bugle sounded,

Our mother’s face rose before our eyes.

Singing this song, the eldest, second, and third sons of farming families marched off to war, sent off with everyone’s encouragement. But one after another, they returned in white wooden boxes wrapped in white cloth. Sobbing, everyone welcomed them home, and yet, on the radio, the news still declared, “Today, the Japanese army has defeated the enemy.” By then, the situation was already desperate, and the people were utterly exhausted.

One day, an order came for everyone to gather at a school or community center. “What could this be?” people wondered. Just before it began, it was announced that the Emperor himself would speak.

Quietly and solemnly, in Emperor Showa’s distinct voice, came the words of defeat:

“To endure the unendurable,

To suffer what is insufferable …”

(This is all I remember.)

I was in fourth grade at the time. Just hearing those words made me realize that he understood our daily hardships, and I cried out loud from the bottom of my heart. The children and adults gathered there wept uncontrollably, not covering their faces. Having endured hunger and survived on wild herbs, all we could do now was cry.

Even today, I vividly remember the atmosphere of that time, and recalling it brings a sharp ache to my heart.

♪ Umi Yukaba (“If I go away to the sea …”)

After the defeat, this song could be heard here and there.

But whenever I hear it, the scenes of those days return, and it remains a sorrowful song I cannot sing without tears.

The Pacific War

December 8, 1941: War begins

August 15, 1945: War ends

We have received handwritten letters from those who participated.